This is a news article that UPD first published on 25th May 2018.

Many people are supportive of using patient data to improve health care and research, but feel they should be asked to give permission first – they would prefer an opt-in or a consent-based system. As the new national data opt-out policy begins to be implemented soon, we set out the difference between these approaches and explain why an opt-out is the preferred approach.

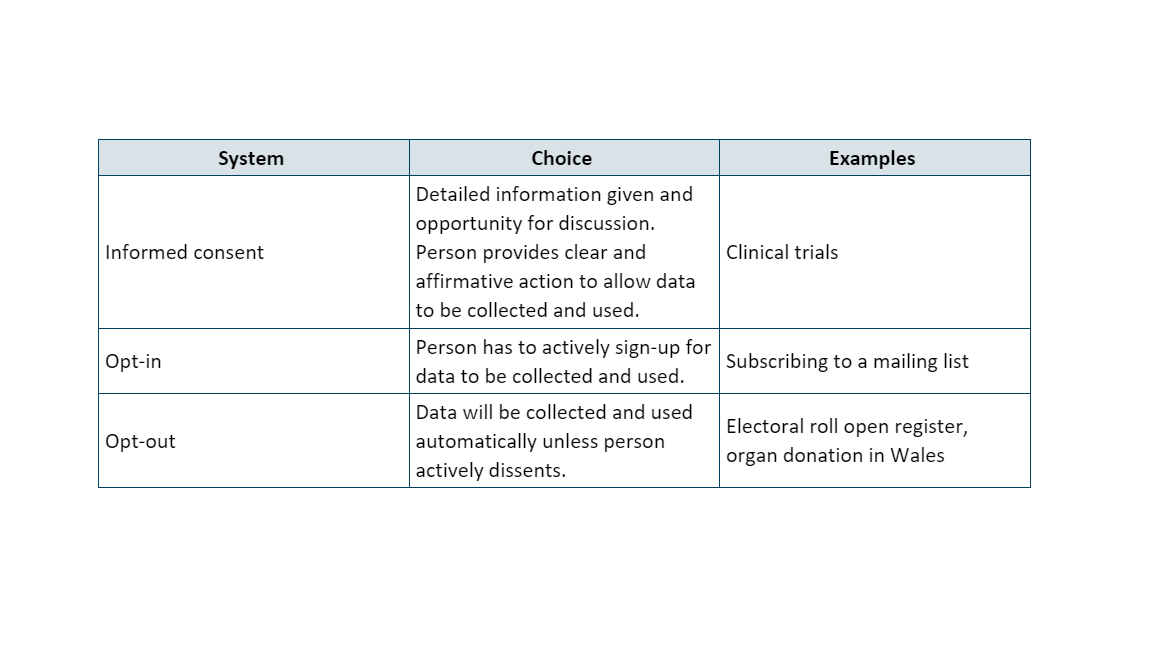

As part of her review into the security and use of NHS data in 2016, the National Data Guardian examined what the most appropriate model for collecting and using patient data across the NHS system would be. After careful consideration, she recommended that an opt-out model be introduced, rather than one based on an opt-in or consent. It’s helpful to be clear on the differences between these approaches:

Doesn’t Data Protection law mean I have to give consent for the data to be used?

It is often assumed that processing of personal data is only possible if the individual has given consent for this to happen. In fact, there are several possible lawful bases for processing personal data, and consent is only one. For many purposes, consent will not be a necessary requirement under data protection law for the data to be used. These include providing healthcare, conducting audits, commissioning services, and undertaking scientific research, provided several conditions about protecting data subjects are met.

Isn’t consent the most ethical approach?

At first glance, gaining informed consent for every use of personal data looks like an ethically sound approach as it puts patients in complete control. It is certainly the right model for research studies such as clinical trials that require active and ongoing participation. However, relying on informed consent for all potential uses of data from patient records would place a disproportionately high burden on patients. From previous research in public dialogues, we’ve found that people initially want to be asked for consent for each instance of data use. But talking through what this means in practice often puts them off the idea, as it’d require frequent contact and engagement that could feel like a hassle.

Alternatively, a data collector could be upfront about all the possible ways the data could be used and seek consent for this broad range all at once. We are all familiar with long terms and conditions that do precisely this. They may in principle be fully informing people, but it is arguable that such “tick and click” consent is not really ‘informed’ and is rather meaningless in practice. This illustrates what happens when too much weight is placed on consent as a mechanism for fulfilling ethical responsibilities towards people’s data. It is not a model that we should hold up as a gold standard for patient data.

Why not use an opt-in?

An opt-in also relies on a person actively indicating that data about them can be used, but is generally “lighter touch” than an informed consent approach.

There are scientific and practical arguments against using an opt-in model for using patient data collected across the healthcare system. For population health research, good coverage across the entire population is essential to ensure that analysis and findings from the data are accurate, unbiased and representative.

With an opt-in model, only the most engaged people who actively take steps to opt-in will be included in the data. Everyone else – including those who are busy coping with their or their loved ones’ health conditions – would be invisible in the analysis. We may also miss the whole story about a health condition, because the data would reflect only a small, selective portion of the population. In some cases there are statistical ways to adjust for missing data, but it is much harder to be sure the research is accurate for different groups if the data is not fully representative.

In contrast, an opt-out system is likely to lead to higher coverage across the population, as it allows the default assumption to be that people are happy for their data to be used. It is likely that relatively few people will actively take steps to opt-out. This is particularly helpful in a diverse population such as the UK, where understanding health differences between, for example, different ethnicities can be an important tool for better prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

What would make an opt-out justifiable?

An opt-out allows people to express a choice, so that if they do object to their confidential patient information being used to improve health, care and services through research and planning, they can say so. But it also ensures that if people don’t express this choice, the data can be used, subject to safeguards and controls on its use. An opt-out system might therefore be the best approach for population health provision and research. This is the conclusion that the National Data Guardian reached after her review.

This does not mean that an opt-out system implemented on its own is a panacea for public confidence. If the healthcare system is going to ask that people have trust in the use of patient data, then transparency, accountability, and a strong case for the public and social benefits of using the data are vital.

In the UK, we do have well-established mechanisms to fulfil these requirements, such as IGARD and CAG. These independent review committees can:

-

provide expert advice on the scientific merit of proposed data uses

-

assess ethical acceptability

-

assess risks

-

determine whether the proposed use is in the public interest, and

-

vet the people and organisations that wish to use data.

They therefore take on some of the ethical responsibility for the data that patients would otherwise individually have to manage in a consent or opt-in based system.

With the national opt-out available, it will be important that:

-

It provides a meaningful, easily accessible choice, together with clear information so that people can be well-informed about the choice they’re making.

-

Patients are not disadvantaged in their care if they decide to opt out.

-

There is good, robust governance for the uses of data. This includes independent oversight and the ability to audit, to ensure data is only ever used in approved ways.

-

Patients can find out about how data is being used in practice.

-

Anyone permitted to use the data is punished if they are found to break the rules.

-

The data is accurate and useful, maximising its value for helping to improve the health and care of the population from which it was gathered.

Taken together and implemented effectively, these steps will help ensure an opt-out approach is more useful, ethical and respectful of patients’ rights than a consent or opt-in system for using patient data.

Find out more about the national data opt-out.