Catherine Bowden, Sarah Devaney and James A. Cunningham, University of Manchester

In this guest blog, Catherine Bowden, Sarah Devaney and James A. Cunningham from the University of Manchester discuss their recent General Practice Data Trust research undertaken with members of the public. They explore issues with the current opt-out system, information provision, feedback loops and the role of educational and communication campaigns.

The recent publication of ‘Uniting the UK’s Health Data: A Huge Opportunity for Society’, a review of the UK health data landscape carried out by Cathie Sudlow, describes health data as ‘critical national infrastructure that can underpin the health of the nation’. We agree that health data can underpin the health of the nation, acting as a valuable resource for developing new treatments, designing effective public health policies, and targeting resources. However, we caution against assuming that it can do this under current conditions.

Ever increasing amounts of health data are routinely collected. The more we come to rely on this wide-ranging data, the more pressing the need to ensure that it is as accurate and representative as possible. Equally, we must ensure that we have the public’s support (as well as the legal basis) for using health data. If not, we risk not only weakening support for health research, but also undermining the relationship of trust between patients and healthcare professionals. This means that we cannot ignore those who currently opt out of sharing their health data for research purposes.

In our General Practice Data Trust research, we have spoken to people who have opted-out of sharing their health data for research purposes to better understand their concerns. Many of our participants feel a strong personal connection to their health data, seeing it as part of their identity and individuality. It plays a part in recording and shaping what it means to be them. Therefore, respecting their views on how and why their health data is used in research is part of respecting them as individuals. All of the people we interviewed in our project wanted to play a part in health research by contributing their data to it, but felt unable to do so under existing regulatory systems and proposals. It is clear that if we want to honour their wish to be part of this important endeavour, we need to address their concerns in any system established to access and share their health data for research.

A key concern for our participants was the one-off, binary nature of the decision they are currently offered over sharing their health data – they can either choose to share all of their data or none of it. This creates a feeling of lack of control and a concern that their data could be used in the future for research that they would not support without them ever knowing what had been achieved with their data.

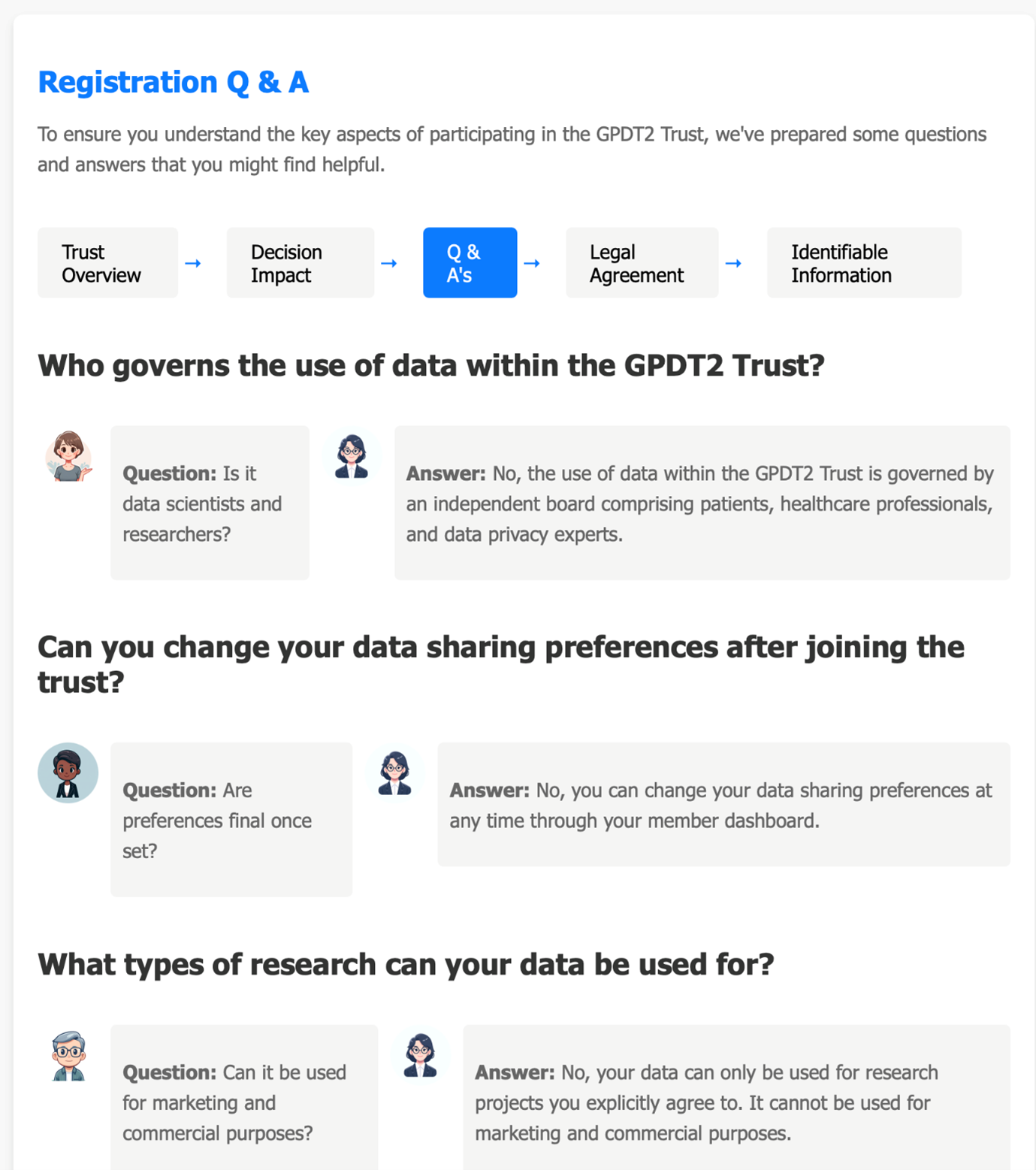

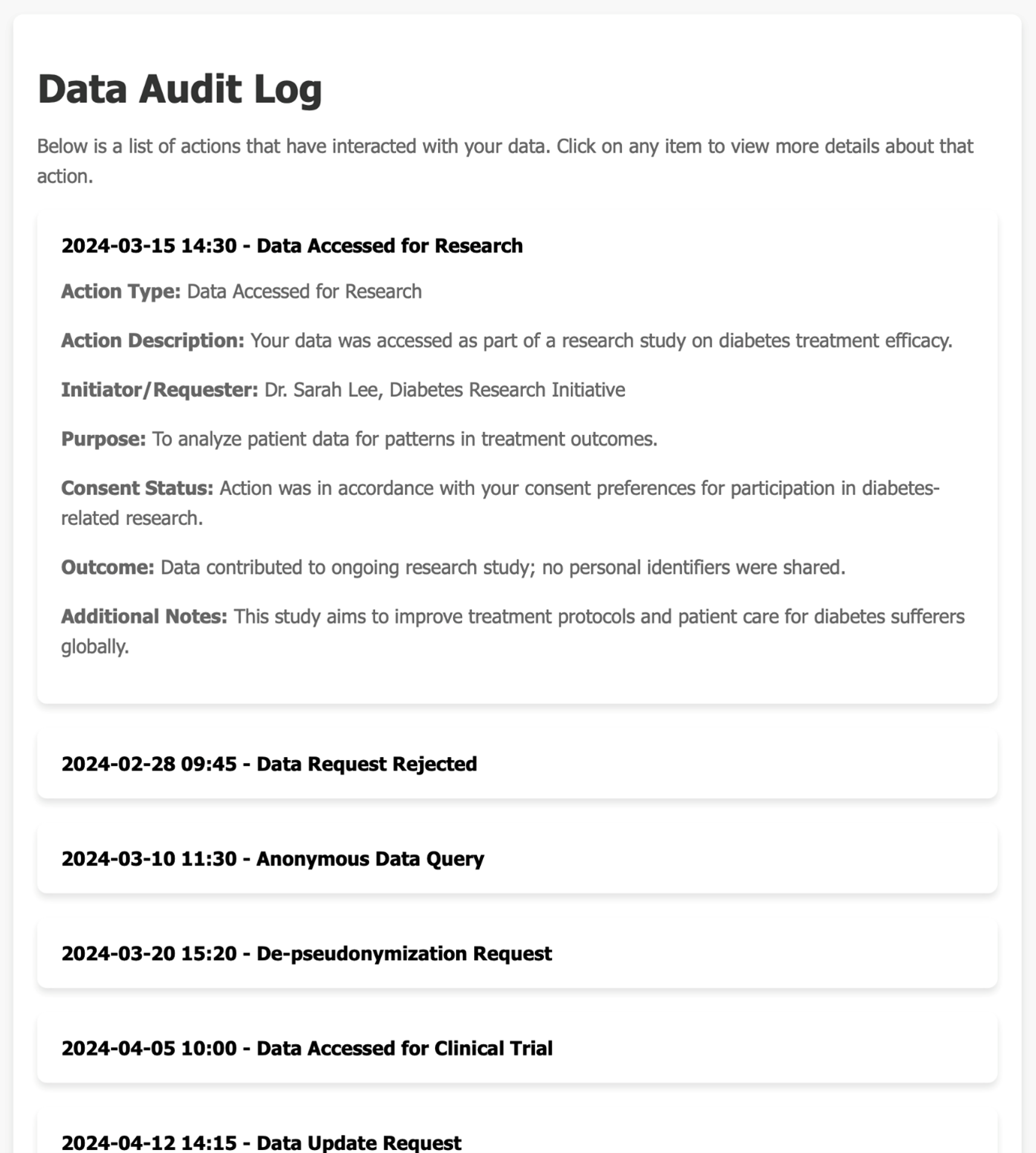

In order to address this, we looked at ways in which information could be provided to people about the research their health data is used for, and how individuals could be given more, ongoing, control over their data. We developed a prototype patient dashboard through which individuals could express their preferences for the types of research their data was used for. Once research had been concluded, they would receive information about the projects that had used their data and what had been achieved. This dashboard was tested in focus groups with UseMYData members, to consider whether this type of interface could offer individuals the control they wanted over their health data.

Participants were supportive of creating a feedback loop about what had been achieved with peoples’ health data and giving people more control over the uses their health data was put to. There was however also a strong feeling that the worries people have over sharing health data with researchers do not always reflect reality. Participants felt that people would be making decisions about sharing their data based on inadequate information. For instance, someone might not be aware of the security measures that were in place and so opt not to share their data for fear of it being passed to insurance companies. Equally, someone might opt not to share their data with commercial organisations, without understanding the roles of commercial organisations and the NHS in the health research landscape.

The clear message from participants was that the current state of public understanding around health data research was not sufficient to ensure that the choices people made would achieve what they thought they would.

If we are to offer people more control over their health data, we have a responsibility to ensure that their choices are properly informed so that these choices reflect their own values and priorities. They need to know, for example, how and why their data will be used, who by, and with what safeguards. They also need to know what the risks are if they do not share their data, and whether the dataset available to researchers is representative of those the research is aimed at helping.

This will require a public health education campaign on a vast scale. Such campaigns are recognised contributors to improving and maintaining citizen health. We strongly believe that a public health campaign on the use of health data for research would be a sound investment in citizens’ health and a tool for improving the efficiency of our health services. Engaging with people about their health data and how it is used in research is not just an opportunity to improve the dataset by reassuring people that sharing will be a safe and ethical choice. It is also an opportunity to learn more about the problems people face in their health, and the health improvements they want their data to be used for. This would make health data research more fit for its purpose of improving and saving lives.

This education campaign needs to begin in schools and be tailored to the needs of a diverse range of groups. After all, there is little point in only educating those who already have access to information about health data research. In this way we can not only ensure that health data is able to underpin citizens’ health, but also empower those who currently lack a voice in shaping their health services by ensuring that such services work for all.

We are grateful to the Data Trusts Initiative for funding the first stage of the General Practice Data Trust work, and the Omidyar Group for funding the second phase.