We're interested in new ways to embed public views and values in decisions about data. A learning approach to data governance may be a useful model to facilitate good decision-making over time.

Why do we need new models of data governance?

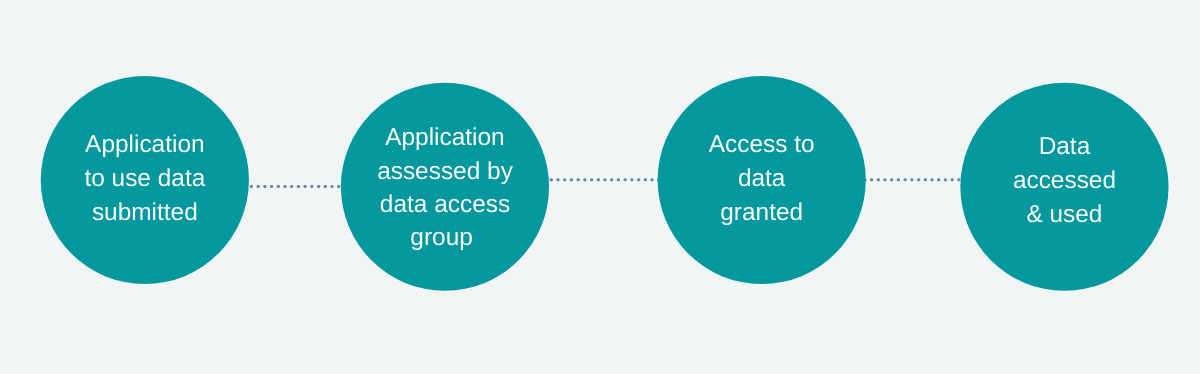

Applications to access health data are usually assessed through a governance mechanism, to make sure data will be used safely and in the ‘public interest’. Examples include NHS Digital’s IGARD and the HRA’s CAG.

But there are aspects of these decision-making processes that make it hard to embed public and patient views in a sustainable way:

-

The decision to allow access to data is often one point in a pipeline, with little (if any) feedback on whether applications achieve their goals.

-

Patient or public membership on these panels can be seen as tokenistic. And as members develop expertise over time, they may become more ‘professionalised’ and less able to play the role of critical friend or representative of patient or public views.

-

“Public interest” changes over time, as new uses of data emerge. There is also not a single public, and the impact of how data is used will vary for different groups. It’s not feasible to explore these nuances in one-off data access decisions.

What’s our idea?

Drawing on insights from our Foundations of Fairness research, we suggest a learning data governance model for data access, shifting from a one-way pipeline to a feedback cycle. The model involves two key ideas:

-

The outcomes from access to data are reported back to the decision-making group (whether the impact is positive, negative, null or unsuccessful).

-

A citizen panel reviews previous data access decisions and their outcomes. It provides feedback to the decision-making group, to inform their future decisions.

This citizen panel:

- Is an addition to public/participant involvement in the existing decision-making process, it does not replace it.

- Could take a range of forms with either a fixed or evolving membership. It could range from an online platform with thousands of participants expressing views on different cases in an ad hoc way, to a group of patients meeting regularly.

- Could draw on a range of evidence to inform its views, from case studies to survey insights.

The citizen panel would aim to answer these types of questions (these are suggestions, not a comprehensive list):

- Did we ask the right questions of the data applicants?

- What (or who) is missing from our decision-making process?

- How should the outcomes of previous projects inform our future thinking on potential risks and benefits from proposals to use data?

- What could help us make better decisions for future applications?

What would be the benefits?

1. Meaningful inclusion: The inclusion of patient and public views is a vital part of the governance process. The panel provides external scrutiny and accountability.

2. Learning from evidence: The panel will know whether the benefits anticipated by previous proposals have actually occurred and can feed that learning into how applications are assessed in future. This could help with spotting overpromise and hype.

3. Dynamic views on ‘public interest’: Public views about data change over time, especially with the development of new technologies. The feedback loop accommodates the fact that what is or isn’t in the public interest is likely to change over time.

4. Minimising risk aversion: Concern about public reaction may be creating risk-averse governance mechanisms. Through learning from insights and critique by the public/participant panel, the decision-making group can have confidence they are asking the right questions. They’ll also have a good grasp of public acceptability and risk tolerance for applications that might be edge cases.

5. Enabling not blocking: The model encourages a shift from viewing governance as a regulatory requirement and a barrier to accessing data, to seeing it as a vital component of trustworthy practice.

What next?

We came up with this idea to encourage further thinking about new ways to involve patients and the public in important decisions about health data. We’d love for this idea to be developed more fully and tested, to see if it’s feasible in practice.

Please get in touch at hello@understandingpatientdata.org.uk if you’d like to talk to us about any of the ideas we’ve raised here.