What is measles and what is happening?

Measles has been in the news recently because there has been an increase in cases in the UK as well as in Europe. It is a highly contagious disease, which is spread by coughs and sneezes.

Health data plays an important part in addressing this problem, by enabling the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) to be able to track the spread of the disease and the health service to respond. These cases have mostly been in England, so this article follows the process in England. Similar activities happen in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

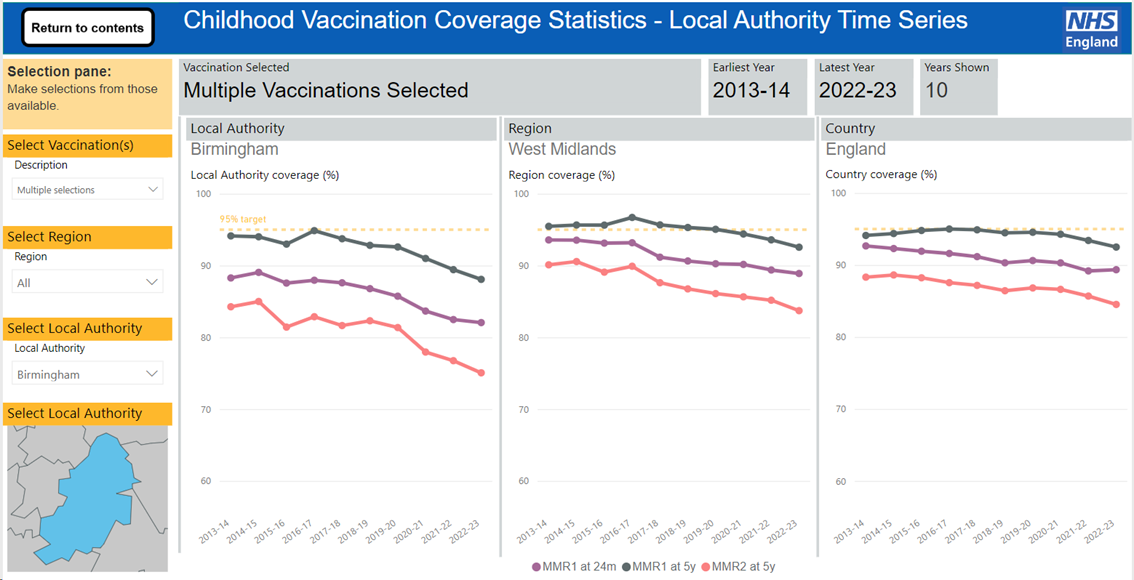

In mid-January in England, official figures show the uptake of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine was at its lowest point in more than a decade (see Figure 1). There are many possible reasons for this. Some people missed routine health appointments during the Covid-19 pandemic, anti-vaccination activism was brought to the fore at this time too, and some people wrongly believe that the vaccine is linked to autism. It is also likely that some people may have underestimated how serious measles is because it had mostly been eradicated in recent years, and decided not to vaccinate their children.

If someone gets measles, their personal health data gets treated carefully. This data plays a significant role in treating someone with measles as well as helping to manage the outbreak.

Figure 1: Vaccination coverage in percentage terms for 1 year olds and 5 year olds, in Birmingham, the West Midlands and England. Birmingham has been particularly affected by an outbreak of measles.

This data has been accessed on a publicly available childhood vaccination coverage statistics dashboard which you can access here. You can see different vaccinations and different parts of England.

The journey of an individual’s data

An individual may contact their GP (or goes to A&E if their symptoms are serious) because they notice they, or their child, has symptoms like a high fever, coughing, sneezing and sore, red and watery eyes.

A doctor will then use their expertise to determine if it’s likely to be measles. They may have a look at the individual’s health record (most of which are now digital), to see whether the child has had the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and whether they had both doses. However, vaccination records aren’t always complete, especially if someone has been vaccinated outside of the NHS (e.g. privately or in another country).

If the doctor thinks it’s measles, they report a ‘suspected case’ to their local Health Protection team, which is part of UKHSA. This is because measles is a ‘notifiable disease’, like Covid-19. A notifiable disease means that it’s a disease listed in the Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010, and sharing information about these diseases is necessary to detect possible outbreaks, initiate contact tracing (to prevent further spreading) and trigger investigation, rapidly.

The information that’s needed is called identifiable data, and it includes personal details about the individual, like their name, address, phone number, when they started to feel symptoms, etc. This information may be shared over the phone, secure email, or through an online system, always with patient data safety in mind.

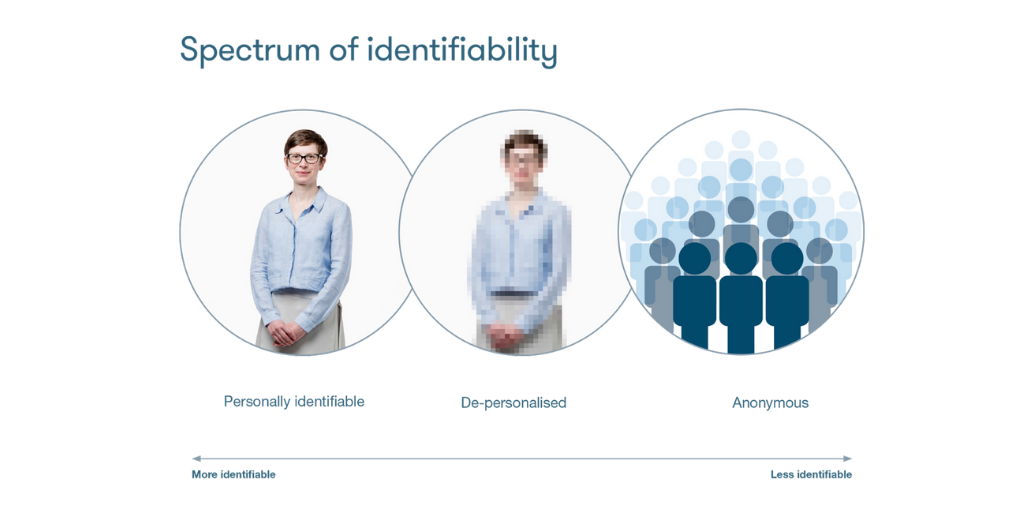

It has to be identifiable data at this stage so healthcare professionals can make sure they are able to contact you if needed, but if it’s used later for analysing the spread of the disease it is likely to be de-identified (where key bits of information are removed to protect your identity). This is allowed in law under The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations.

Figure 2: UPD’s visual demonstration of identifiable, de-personalised and anonymous information

To confirm whether this is definitely a case of measles, a sample (e.g. saliva) needs to be taken which can be analysed further in a lab (e.g., an NHS lab in a hospital or a UK Health Security Agency lab). These samples may be collected by healthcare professionals, or they may be collected through self-administered testing kits (similar to Covid-19 home testing kits).

Once the sample has been tested in the lab, the machine provides data about what it has detected. Legally, under the Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010, all positive results have to be reported to UKHSA, and this is then considered a ‘confirmed case’. Negative or void results are often reported to UKHSA too, and it’s helpful to do so to support the response, know how many ‘suspected’ cases were not confirmed to be measles, and to monitor whether the UK is meeting the World Health Organisation’s measles elimination targets. The test result may be recorded in your health record.

Once the sample has been tested in the lab, the machine provides data about what it has detected. Legally, under the Health Protection (Notification) Regulations 2010, all positive results have to be reported to UKHSA, and this is then considered a ‘confirmed case’. Negative or void results are often reported to UKHSA too, and it’s helpful to do so to support the response, know how many ‘suspected’ cases were not confirmed to be measles, and to monitor whether the UK is meeting the World Health Organisation’s measles elimination targets. The test result may be recorded in your health record.

UKHSA might ask the doctor, or individual, to do some ‘enhanced surveillance’. Surveillance is the word used to monitor infectious diseases by analysing data, and enhanced means that there is more surveillance than usual. This might include answering some additional questions in a survey that could be relevant to identifying the source of the outbreak, and developing public health advice to help limit the number of people that become infected.

At a national level, the initial notification data, lab data, and survey data come together alongside hospital data and vaccination data to monitor the outbreak of the disease in a de-identified way. This means key identifying bits of information, like someone’s name, are taken out. It could be used to determine the ‘R’ number (reproduction number), which calculates how many people one person is likely to infect, helping to predict the spread. It could also be used to identify trends in who is getting infected, so more help can be provided. At a local level, data will be used to help provide individual care and help the local NHS prepare and respond.

Aggregated data (anonymised data about multiple people) is published regularly, so that it’s available to the media, researchers and members of the public. This information can be found on these links:

Other useful links:

- Page updated: 3 February 2025

- Print page